"In international climate negotiations, the Philippines has one of the strongest voices demanding climate justice. Ironically, justice is being denied to hundreds of communities living in the shadow of coal-powered plants. The country truly needs additional funding assistance to help our people and communities adapt to the impacts of climate change. But the moral power of that position is severely undermined by our decision-makers’ myopic obsession with coal."

By Anna Abad

Philippine Daily Inquirer

Monday, October 29th, 2012

IN 2011, the Philippines topped the list of the most disaster-prone countries in the world.

The distinction is confirmed by the series of weather-related calamities that was endured by the country last year, and which claimed over 3,000 lives, affected 15.3 million Filipinos, and resulted in economic losses of over P26 billion. It is a narrative that we have all become familiar with—that the Philippines is one of the countries most vulnerable yet least prepared to deal with the anticipated and escalating impacts of climate change.

The words “unprecedented” and “extreme” are often heard nowadays. Unprecedented amount of rainfall, unprecedented flooding, unprecedented melting of the ice, extreme weather, extreme drought. If everything that’s happening to our planet today has reached the point of superlatives, I fear what’s in store for our future.

In the absence of bold and dramatic action to reverse global warming, climate scientists warn that the pattern of extreme weather that we have been experiencing in recent times is likely to become the new “normal.”

While the greatest share of the responsibility to avert this crisis falls on the industrialized countries, it should not be construed as an excuse or a license for developing countries to continue mimicking the destructive path that is pushing the climate to a tipping point from which the world may never recover.

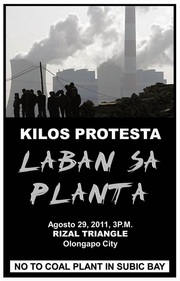

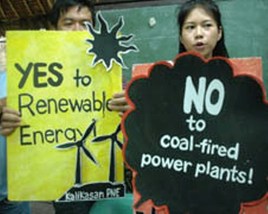

The burgeoning power crisis in the Philippines is the latest terrain where we see this dynamics at play. Despite the abundance of sources of clean and renewable energy (RE) in the country, President Aquino and his Department of Energy (DOE) have succumbed to converting the Philippines into a hotbed for dirty energy by anchoring its energy future on polluting and climate-destroying coal power plants.

The decisions now being made by the government—particularly the facilitated approval of a string of coal-fired power projects in Bataan, Batangas, Zambales, Palawan, Negros, Iloilo, Cebu, Davao, Davao del Sur, Misamis Oriental, Sarangani and Zamboanga—present a major setback in the Philippines’ quest to attain energy independence by harnessing sustainable and renewable energy sources. Instead of constructing coal-fired power stations that take three to four years to complete, and that continue to perpetuate our dependence on finite and price-volatile fossil fuels, the country will be better off making the decisive transition to RE systems now. Compared to coal-fired plants, such systems take less time to build, and their fuel supply is virtually free and limitless. They are, moreover, exempt from the quirks and instability of a fluctuating market.

By Anna Abad

Philippine Daily Inquirer

Monday, October 29th, 2012

IN 2011, the Philippines topped the list of the most disaster-prone countries in the world.

The distinction is confirmed by the series of weather-related calamities that was endured by the country last year, and which claimed over 3,000 lives, affected 15.3 million Filipinos, and resulted in economic losses of over P26 billion. It is a narrative that we have all become familiar with—that the Philippines is one of the countries most vulnerable yet least prepared to deal with the anticipated and escalating impacts of climate change.

The words “unprecedented” and “extreme” are often heard nowadays. Unprecedented amount of rainfall, unprecedented flooding, unprecedented melting of the ice, extreme weather, extreme drought. If everything that’s happening to our planet today has reached the point of superlatives, I fear what’s in store for our future.

In the absence of bold and dramatic action to reverse global warming, climate scientists warn that the pattern of extreme weather that we have been experiencing in recent times is likely to become the new “normal.”

While the greatest share of the responsibility to avert this crisis falls on the industrialized countries, it should not be construed as an excuse or a license for developing countries to continue mimicking the destructive path that is pushing the climate to a tipping point from which the world may never recover.

The burgeoning power crisis in the Philippines is the latest terrain where we see this dynamics at play. Despite the abundance of sources of clean and renewable energy (RE) in the country, President Aquino and his Department of Energy (DOE) have succumbed to converting the Philippines into a hotbed for dirty energy by anchoring its energy future on polluting and climate-destroying coal power plants.

The decisions now being made by the government—particularly the facilitated approval of a string of coal-fired power projects in Bataan, Batangas, Zambales, Palawan, Negros, Iloilo, Cebu, Davao, Davao del Sur, Misamis Oriental, Sarangani and Zamboanga—present a major setback in the Philippines’ quest to attain energy independence by harnessing sustainable and renewable energy sources. Instead of constructing coal-fired power stations that take three to four years to complete, and that continue to perpetuate our dependence on finite and price-volatile fossil fuels, the country will be better off making the decisive transition to RE systems now. Compared to coal-fired plants, such systems take less time to build, and their fuel supply is virtually free and limitless. They are, moreover, exempt from the quirks and instability of a fluctuating market.

One model we should examine is found in Germany, where extensive hybrid systems called “Renewable-Energy Combined Cycle Power Stations” are already up and running. This system relies on an integrated network of wind, solar, biomass and hydropower installations spread across the country. With this system, one can quickly adapt to variations in supply in any one resource by drawing on others.

In the Philippine National Renewable Energy Plan, the long-term goal includes a 100-percent increase in RE-based capacity by 2030. Given this glowing resource prognosis for RE, government planners will do well to replicate positive experiences elsewhere, instead of insisting on an already discredited model.

In Japan, for example, following the government’s announcement of the approved feed-in tariffs, electronics conglomerate Toshiba will be bringing in an investment worth $379.6 million to build large-scale solar plants. More clean-energy investment is expected to bring in billions of dollars into that country.

The DOE has awarded 313 renewable energy service contracts but to this day, not one has been developed. The fate of these projects lies in the hands of the DOE, which has yet to establish the eligibility criteria for renewable energy developers to proceed. More than three years after its passage, the Renewable Energy Law remains a paper promise.

In international climate negotiations, the Philippines has one of the strongest voices demanding climate justice. Ironically, justice is being denied to hundreds of communities living in the shadow of coal-powered plants. The country truly needs additional funding assistance to help our people and communities adapt to the impacts of climate change. But the moral power of that position is severely undermined by our decision-makers’ myopic obsession with coal.

Scientist Jim Hansen of the United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration neatly describes this predilection for making ill-advised decisions as an injustice similar to “storing up expensive and destructive consequences for society in the future.”

We have a real opportunity to set things right. We need strong, strategic and visionary leadership to advance real solutions instead of impetuous decision-making that exacerbates the roots of the climate crisis.

In this era of climate change, it is but appropriate for the people to expect their leaders to make decisions to move our societies toward the right direction. Investing in coal takes us back to the 19th century. Embracing renewable energy now advances us to the future. Aside from guaranteeing our energy security and independence, the latter also fortifies the demands by impacted countries and communities for climate justice.

In the final analysis, this is a moral choice that President Aquino has to make.

(Anna Abad is the climate and energy campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.)

Re-posted from: Philippine Daily Inquirer

In the Philippine National Renewable Energy Plan, the long-term goal includes a 100-percent increase in RE-based capacity by 2030. Given this glowing resource prognosis for RE, government planners will do well to replicate positive experiences elsewhere, instead of insisting on an already discredited model.

In Japan, for example, following the government’s announcement of the approved feed-in tariffs, electronics conglomerate Toshiba will be bringing in an investment worth $379.6 million to build large-scale solar plants. More clean-energy investment is expected to bring in billions of dollars into that country.

The DOE has awarded 313 renewable energy service contracts but to this day, not one has been developed. The fate of these projects lies in the hands of the DOE, which has yet to establish the eligibility criteria for renewable energy developers to proceed. More than three years after its passage, the Renewable Energy Law remains a paper promise.

In international climate negotiations, the Philippines has one of the strongest voices demanding climate justice. Ironically, justice is being denied to hundreds of communities living in the shadow of coal-powered plants. The country truly needs additional funding assistance to help our people and communities adapt to the impacts of climate change. But the moral power of that position is severely undermined by our decision-makers’ myopic obsession with coal.

Scientist Jim Hansen of the United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration neatly describes this predilection for making ill-advised decisions as an injustice similar to “storing up expensive and destructive consequences for society in the future.”

We have a real opportunity to set things right. We need strong, strategic and visionary leadership to advance real solutions instead of impetuous decision-making that exacerbates the roots of the climate crisis.

In this era of climate change, it is but appropriate for the people to expect their leaders to make decisions to move our societies toward the right direction. Investing in coal takes us back to the 19th century. Embracing renewable energy now advances us to the future. Aside from guaranteeing our energy security and independence, the latter also fortifies the demands by impacted countries and communities for climate justice.

In the final analysis, this is a moral choice that President Aquino has to make.

(Anna Abad is the climate and energy campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.)

Re-posted from: Philippine Daily Inquirer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed